Gradually, then suddenly

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

Last week I introduced you to the low correlation lie, and explained how it blinds investors from the actual risk in their portfolios. In that piece I explained

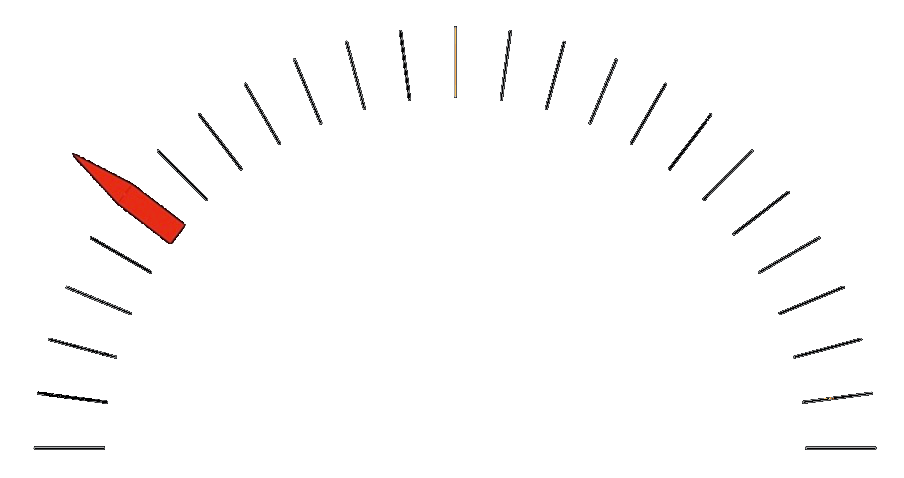

…private market assets are valued infrequently. At best once a month, but often only once a quarter or even every six months to a year. And these valuations require a lot of judgment, potentially ignoring factors that the valuation professional decides are temporary, or transitory… Meanwhile, your public market investments are granted no such grace. They are valued daily—in fact, multiple times each second—by the individuals trading them… This gives private investments the illusion of low volatility relative to public market investments.

Like driving down the highway blindfolded, this can be a dangerous endeavour, and you can remain blissfully unaware until it’s too late. Also, why would you want to do it when you can just take the blindfold off?

I will use a recent example to illustrate how private equity funds can hide what’s really happening under the surface. Southland Royalty, an oil and gas producer owned by EnCap Investments, a private equity firm, collapsed in late 2019. This by itself is unremarkable. It was a tough environment for US energy producers. What’s notable is how the collapse was reflected at the fund level.

As late as October 2019, EnCap valued their interest in Southland at $773.7 million. At the December report, the investment was marked down to zero. What happened in those fateful last two months? Nothing, really. Other than it became quickly clear that EnCap’s valuation team had woefully overestimated the value of their holding in Southland.

It’s derisively called “mark to myth” and “mark to make-believe” accounting, and it’s a real problem for private assets that don’t trade on an active market. It means there is often risk lurking that you don’t see. It’s fair to say that if Southland was trading on public markets, the price would have reflected the deterioration in its business as savvy money managers and insiders dumped their shares. Without that signal, you get a fund manager who believes that it’s worth 99 percent of cost a mere two months before it goes bankrupt.

This sounds like an outlier example, but sadly, it isn’t. Over the years I have seen this a few times. Even as recently as this young calendar year I encountered an investment statement illustrating a fund that was almost fully valued as recently as December 31, 2023… now marked down to zero.

The reality is that most of the time the volatility in a company’s stock price doesn’t result in bankruptcy. It bounces back. The storm passes. The cycle turns. And so while publicly traded assets appear to be more volatile than private funds, it’s just an illusion.

Now ask yourself this question: Would you ever tolerate such obfuscation in your own business? Would you have survived over the years if you did? Would you allow your managers to fudge results and hide “temporary” impairments from you on the basis that they were short term in nature?

Of course not.

Now why would you allow it in your investment portfolio?