Holding through apocalypse

“If only I had invested in Amazon back in the ‘90s,” you may have uttered at one point or another.

Let’s play a game. Let’s pretend you did.

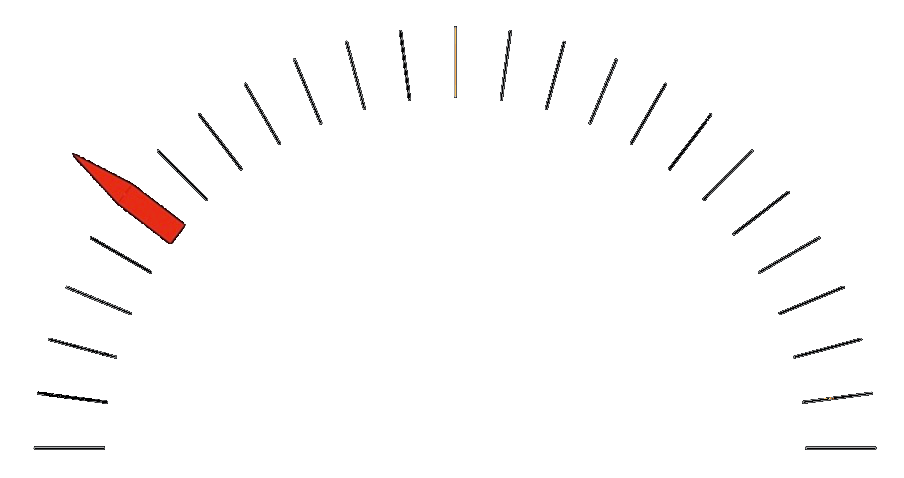

If you invested in the company at any time in the 1990s, you were subject to severe drawdowns—on a few occasions seeing 50 percent of the value of your investment in the company disappear. You would have had to hold on through those drops. But they were just an appetizer for what was to come. The dot-com bubble popped in March of 2000, but there was no quick bounceback like the ones you had become accustomed to. Instead, the stock continued to sink. Every attempt to rally was met with more selling. There was no sign of a bottom and the stock price drifted lower… you were down 50 percent, then 60 percent, then 70 percent.

As traders tried to catch a bottom in the stock price, they were reminded of that old bit of dark stock market humor—that every stock down 90 percent was once a stock down 80 percent…that was again cut in half.

So what awaited investors next, while stocks struggled to recover ground lost in the crash? Only the horrific events of September 11, 2001, which shocked the world while shaking confidence in the economy and the stock market.

There was a capitulation of sorts, with investors fleeing all stocks, but particularly those that were perceived as more risky. And thanks to a high valuation and a lack of profits, Amazon fell handily into that bucket.

On September 29, 2001, the shares reached a nadir, down 95 percent from their peak in December 1999.

Let that sink in. Down 95 percent.

Even before the public experienced the horrors of 9/11 and the uncertainty it would bring, investors were questioning the path the company was on. A Bloomberg article published not long earlier quoted a hedge fund manager who had the following to say about the company: “They’re still losing money and are likely to continue to do so for the foreseeable future,” and “It’s up in the air whether their business model will work.”

Barron’s in 1999 featured a famous “Amazon.Bomb” cover story in which they called Amazon “just another middleman, and the stock market is beginning to catch on to that fact.”

So you’re holding on to Amazon. You think you’re a believer in the business model and the leadership. But you’re reading this kind of commentary in the media. And you’ve watched almost your entire investment in the company evaporate into thin air.

Did you keep holding?

Did you buy more?

Or more likely, at some point during the inexorable decline, did you decide you were wrong, capitulate, and sell it to end the pain?

Maybe you had the fortitude to hold it all the way down. Let’s be honest. As it clawed its way back up, you very likely sold, happy to recover 10 percent, 20 percent, or 30 percent of the capital you put in, just glad that you were able to sell it for something.

Did you really think that the company would ever recover its peak? A stock down 95 percent has to go up 20x just for you to break even. And this is a company burning money every quarter, that other investors were giving up on en masse. Was a 20x return realistically in the cards? Did anyone without the last name Bezos actually survive the crash and faithfully hold all the way back up?

This is another reason why volatility is a killer.

It leads you to make horrible decisions.

If you can ignore it, that would certainly help. Some volatility is easier to ignore than others, though, and a 95 percent decline in a company that the mainstream financial media are expecting to fail is hard to ignore for almost everyone.

Even better than putting yourself in a position to have to ignore extreme volatility such as this is avoiding it in the first place.

Yes, if you bought and held Amazon stock you may have had a lot more financial wealth today. But the odds that you would have done so are essentially zero. If you held a portfolio of less volatile stocks that were already profitable, the chances that you would have held through the downturns are far higher.

I like to say that the only two numbers that matter are the price at which you buy and the price at which you sell. But the path between those two points can make all the difference in whether you’re able to hold on for the long run. When you buy one of these crazy expensive stocks on the promise of future growth, you need to be prepared to hold through 90 percent drawdowns. It’s not an easy mental space to be in, but it’s what you need to do if you’re buying for the long run.

Professional investors struggle with volatility as much as anyone. The only difference is that they’re aware of it and try to take steps to mitigate it. I got a kick out of a 2020 interview with Jim Rogers. When asked how he focused on long-term outcomes, he replied, “I don’t pay attention. Once I was investing somewhere, I think in an African country. The broker asked how often I wanted to receive reports. I said, ‘Never send me any prices. I don’t want to know. Because if they go up, I might sell. And if they go down, I might panic and sell. I don’t want to know. I’m making a basic, fundamental, long-term judgment here that I expect in a few years this is going to make a lot of money. So don’t send me the prices.’” Speaking about another one of his positions, he said, “I couldn’t tell you the price of Aeroflot today. And I don’t want to know. Don’t tell me.”

I’m telling you to ignore the deception of volatility, but as you can tell from Jim Rogers pleading with his broker, it’s easier said than done. It’s instructive to see the extent to which he is willing to go in an attempt to overcome his weaknesses—weaknesses that we all share. Compare this to the investment committees who grade portfolios every three months, or the investor who checks his portfolio performance each day (or multiple times each day!). Understand how harmful those activities are, and how they leave you susceptible to making mistakes.

Market prices can create a feedback loop in the investor’s mind. The news is bad, and stock prices are falling, which confirms your fears, which causes investors to sell, which sends stock prices lower. The mental process of breaking that feedback loop is difficult for even the most experienced investors.