The Venture Lottery

You've gotta ask yourself a question: "Do I feel lucky?" Well, do ya, punk?

- Detective Harry Callahan

One of the areas that open up for you if you’re wealthy is private equity. Not only in the form of funds, but, more interestingly, also in the form of direct investments in the companies themselves. Most often, this involves early-stage venture investing. Why? Because these are the companies out there raising funds. More mature, profitable private firms are self-financing, and those looking to raise capital can do so through institutional investors on more favorable terms, rather than going directly to private individuals.

Let’s say for a moment that there’s an exclusive investment that not just anyone can get into. You have to know someone. Also, they’re not accepting any checks below $150,000.

There are some other really famous investors who are in it. Maybe a few names you hear on CNBC. Maybe a few really high-profile local people you’d love to network with. You might run into them at the shareholder meeting!

Imagine if you had invested in Google before the IPO! This company might be the next Google!

The founders are brilliant. One of them is the guy who invented the Amazon “Buy It Now” button!

Let’s face it, this is exciting. I just made up this fictitious company, and even I would be excited about investing in it.

Being an investor on the ground floor of a rocket ship, hitching your wagon to the next all-star CEO, and celebrating success with a close-knit group of investors sounds thrilling. And it’s great cocktail party fodder. Is it any surprise that this is a huge attraction for entrepreneurs with liquid wealth?

However, this area is the Wild West of investing. The rules are different. The stakes are higher. And your dreams rarely match up with reality.

When a publicly traded stock investment goes bad, you can sell the stock, take a loss, and wipe your hands of the whole fiasco. But when a private investment goes off track, you can find yourself stuck. Worse, if you are the “deep pockets” in the investor group, you may be called upon to provide emergency financing to rescue the company (and to protect your initial investment).

In business school they teach you that the legal corporate ownership structure means that creditors can’t go after shareholders beyond the value of their investment in the company. So as a shareholder, your theoretical maximum loss is 100 percent. When it comes to private equity, and the potential need to fund future equity rounds, your ultimate losses might actually turn out to be several times your initial investment. I’ve seen this play out many times.

Being a minority investor in the wrong private company can be a unique form of torture. Your rights are limited. Your ability to sell is limited. I’ve watched founders fight each other, watched C-suite leadership fight with engineers, and watched CEOs lose their jobs and set up a competing company the next day. All with shareholder money on the line. If you own a minority stake in the company while all of this is happening, you may have no choice but to sit by and watch helplessly as the drama plays itself out. Sometimes it happens behind the scenes, and all you hear are rumors and whispers, leaving you unable to find out what’s really going on. Or, perhaps worse, you get entangled in the political struggle between the warring factions. I know more than one “retired” investor who had to unretire to take over a floundering investment after leadership abandoned the project. It’s not fun.

Following high profile investors into venture investments is also a common mistake. You might have a few such investments in your portfolio, but you need to realize that the person whose coattail you’re riding on might have hundreds of such investments, and expects the vast majority of them to fail.

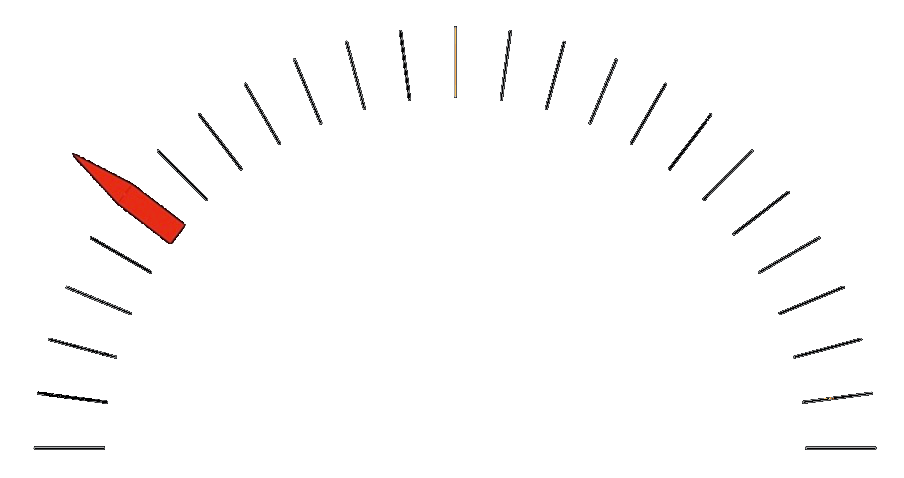

Let’s use the example of Masayoshi Son, head of Japanese firm SoftBank, who has tech investments around the globe. A New Yorker article quoted a former SoftBank executive as saying, “Venture capital has become a lottery. Masa is not a particularly deep thinker, but he has one strength: he’s devoted to buying more lottery tickets than anyone else.”

Photo by dylan nolte on Unsplash

Early-stage private equity sounds exciting, sexy, and profitable. It can be all of those things. But more likely it will be none of those things. It can be a headache, involve costly legal battles, and tie up your cash for years, even decades.

And the investment performance? Well, it’s a mixed bag. The best can do very well, thanks to connections and a platform through which they can promote their investments. Most others struggle mightily. The dispersion of returns is huge. At the end of the day, these are all just very expensive lottery tickets, and implementing the strategy properly means that you need to own a lot of them. It’s hard to do this as a side gig, or as a non-institutional investor allocating a limited amount of money to the area for “uncorrelated returns.” Seasoned angel investors can enter into hundreds of deals over the years, and so I implore you: understand the commitment you’re getting yourself into. It’s a full-time business… and a messy one at that.

Investment legend Charles D. Ellis summarized it nicely in an interview with Bloomberg: “Usually 90 percent of the great successes in venture investing go back to those same ten or dozen organizations. And success breeds success, which breeds success. So you’re either one of the favorite investors, or you shouldn’t consider venture investing, because you will not succeed.”

I hate to sound overly negative, but it’s best to approach the idea of investing in private companies, especially early stage and venture, with your eyes wide open. If after reading all of this you are still raring to go, then you might be the type of person who should be doing this type of investing. Go for it! As always, I advise my clients to limit their exposure and to make sure that the bulk of their wealth is in a safe basket of mature equities.

So… do you feel lucky?