Strong Opinions, Loosely Held

In Low Risk Rules I write about the importance of conviction to the investment process. Knowing what you own and why you own it helps you hang on when things are at their worst, and in fact, to buy more when everyone else is selling. It’s a key element to generating a long-term record of outperformance.

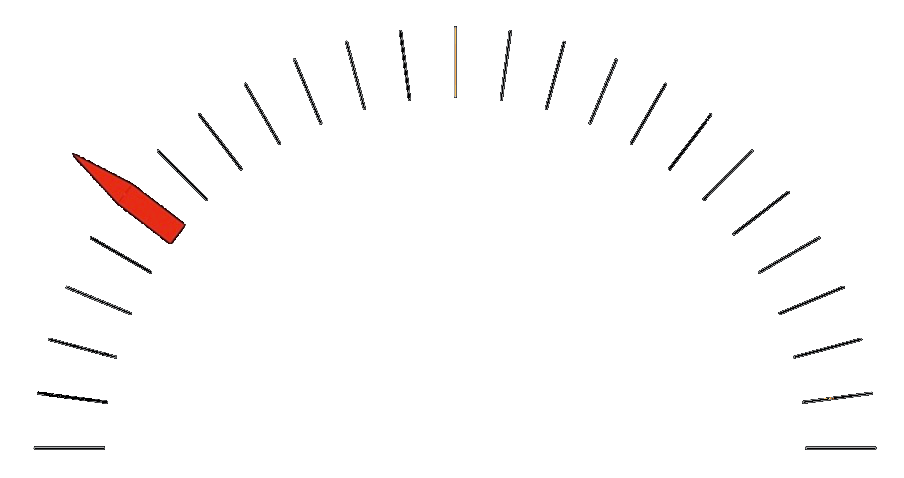

But conviction can be a double-edged sword. While it’s a necessary ingredient to staying the course when everyone around you is panicking, it can also mean that you’re wrong and unwilling to accept any contrary information—firmly entrenching yourself in a losing position.

It’s hard to change your mind when you have publicly taken a particular stand on a topic - any topic. And this can be costly. It takes special effort to prevent it from infecting your investment portfolio.

While you want your investment managers to have confidence in their research and methods, you also want them to exhibit a good degree of humility and to be able to admit when they are wrong. This is the balance of confidence and humility that every great investment manager needs to achieve.

I’ve seen far too many portfolios die at the altar of a stubborn belief in rising inflation, interest rates, gold prices, or, worst of all, a strategy dependent on anticipating another market crash—another 1929, 1974, or 2000. If your portfolio’s success depends on events that take place only a few times each century, you are on the wrong path, playing a low-probability game.

A manager who has committed publicly to a strong opinion on a certain asset (for example, “oil is going to $200 a barrel” or “the US dollar will inevitably collapse”) is a huge red flag. Once you have publicly, and often very visibly, committed yourself to a certain viewpoint, it becomes far more difficult to disavow this position in the future without losing face. You’ll find that money managers in this position will often stick to their public views far longer than they should, ignoring any contrary evidence, if only to refuse to admit they were wrong. Don’t let their ego take you along for the ride.

This past week Morgan Housel wrote a post about this, titled “Mental Liquidity,” which he describes as “the ability to quickly abandon previous beliefs when the world changes or when you come across new information.”

From his article:

So much of what people call “conviction” is actually a willful disregard for facts that might change their minds. It’s dangerous because conviction feels like a good attribute, while its opposite – being wishy-washy – makes you feel and sound like an idiot.

Beliefs take effort and investment, and it hurts to realize that there may be limited ROI on your hard-fought convictions. For a lot of things in life – particularly politics, investing, and relationships – people don’t necessarily want the truth; they want certainty. Changing your mind is hard because it’s an admission that the certainty you once thought you held was an illusion. The path of least resistance is to cling to beliefs for dear life.

There are so many ways in which human psychology stands in the way of investment success. This is one of the big ones.

Some people are a bit surprised and disappointed when I answer “I don’t know” to the question of what’s going to happen to the market. Of course I have an expectation in my mind, a balance of probabilities that adjusts as new information comes out and changes my assumptions. But I don’t like to commit publicly to these views, because that makes it more likely that I will continue to hold onto them even if evidence presents itself that I’m wrong.

That is one reason why you won’t see me making any predictions or stock picks in this blog (sorry!)

I don’t want to publicly commit to an idea because I know that will make me less likely to disavow it in the future. And that’s a dangerous world for an investment manager to live in.

If you recognize this reference, congrats, you’re old like me.

I remember seeing a portfolio manager’s slide deck back around 2010. Although he presented himself as a fundamental value manager, one of his main ideas, written right there in bold letters, was that gold would hit $3000 an ounce. And it doesn’t matter whether I agreed with him or not; seeing that commitment in his presentation signalled a huge red flag for me. Because once you’ve very publicly proclaimed that gold is going to $3k an ounce, it’s hard to walk that back.

And that makes it more likely that you will stick with your thesis for too long. Your ego will end up costing your investors precious capital.

So when someone asks me what’s going to happen to interest rates, or the price of oil or Bitcoin, I say “I don’t know.”

It’s not a copout. It’s a necessary ingredient to successfully managing my clients’ capital by keeping my own ego out of the way.