Chasing hundred-baggers

For years, I kept an old stock certificate by my desk as a reminder of how I got lucky… and how overconfidence was my undoing.

The story goes like this: A young investment geek, as soon as I was old enough I made an appointment with my bank and opened up a trading account. My first stock purchase was a quick bust, but I consider it tuition well spent. Like a child touching a hot stove, it taught me well. I had some big winners in my first few years of investing… stocks that doubled or tripled in short order. That emboldened me, and set me up for a life-changing investment.

I was in university, second or third year, sitting in a compulsory Information Technology course. One of the topics being covered was the potentially world-changing hardware being laid down on ocean floors across the globe: fiber optic cables. For some reason, it’s burned in my memory - I can recall the pictures in the textbook, bottom of the left-facing page - the stock photo of fiber optic cables lit up in the spectrum of colours, along with a photo of workers in a clean room assembling the amplification equipment.

I read the local newspaper each day, a habit I had since I was around 10 (I was an odd child). The younger version of me focused on sports and entertainment, but by this point I was lingering on the business section. And so it was that I familiarized myself with a small local company that had recently issued shares to the public for the first time.

JDS Fitel manufactured equipment that multiplied the capacity of fiber optic cables. Once a communications company invested to lay the wires across ocean floors around the world, JDS equipment promised to exponentially multiply the capacity of those cables.

I saw this young company, with no debt, doubling revenue every year, had just gone public, and I could own a piece of it for around 30x earnings. It was expensive, but in my mind, not unreasonable given the expected growth. At the time I was reading Robert Hagstrom’s “The Warren Buffett Way,” and faithfully reproduced the valuation model that Hagstrom used to explain Buffett’s thought process. JDS looked like a winner.

I put an irresponsibly large chunk of my portfolio into it. That moment of youthful exuberance somehow turned into one of the best financial decisions I have ever made. As the company grew and merged with San Jose based powerhouse Uniphase, it found itself in the middle of a communications revolution and a stock market bubble. And I rode it up, occasionally selling shares.

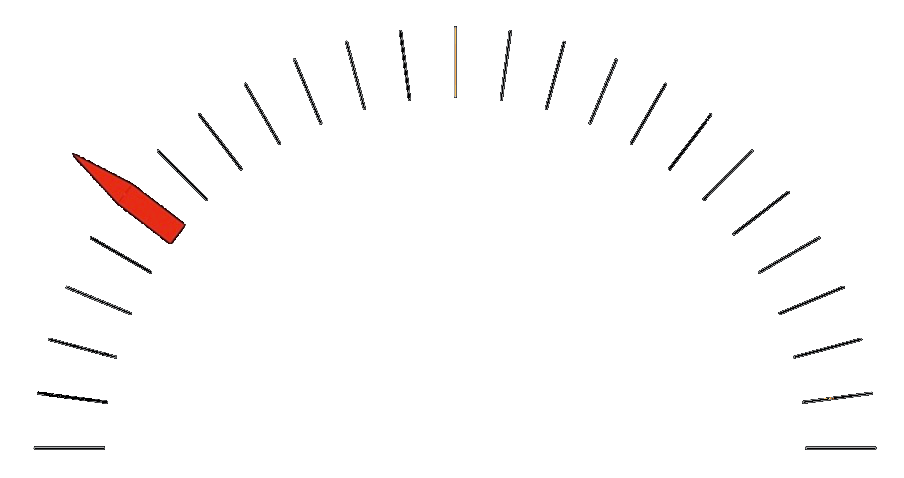

Each time I sold, I would come to regret it. The stock was riding an exponential curve. Even though I knew it wasn’t sustainable, it felt like selling was a dumb move. Maybe prudent in the long run, but dumb in the short run. From my purchase price to the peak, the stock was up over 60x.

Source: stockcharts.com

I took the gains harvested from JDS and invested them into various other companies. I thought I was clever because I was selling the stock of a company trading at 50x revenue and buying a company selling at 40x revenue. In retrospect, it was lunacy. But that’s what drives market bubbles.

I was addicted to the rush of investing in a big winner. Eventually, I identified my next big target. The next JDS. It was a company called Global Crossing. A company that was building out a communications network around the world, and would be able to use technology to multiply the bandwidth available on its network. It was going to disrupt the old telcos, with their legacy analog phone lines. They were toast.

I put my own money in Global Crossing. I told friends and family to put money into it. After seeing how well I did in JDS, they were quick to follow me. And soon after, it began a long and painful descent.

“People don’t get it,” I reasoned, parroting the analysis I saw online. “These guys aren’t making money now, but they are investing in a network that will be a money machine in the future. They are going to destroy the incumbent networks.”

And while I bought more, on “sale,” the stock continued its steady decline.

Global Crossing was eventually a zero. Bankruptcy was inevitable and obvious to anyone objectively looking at the financial statements. I had rolled a good amount of my JDS profits into this company and vaporized them.

As a final, poetic move, I requested the worthless Global Crossing stock certificate from my discount brokerage. I wanted it to serve as a reminder of what can happen when you don’t know what you’re doing. When you lose your discipline. When you get greedy.

I was charged $49 to have it processed and mailed out to me. I had the intention of framing it and hanging it on a wall, but never got around to it. I wanted to snap a picture of it for this article, but as a final insult, I can’t even find the damn thing.

And that's how I lost more than 100% of my investment in Global Crossing.