Mr. Market in the mirror

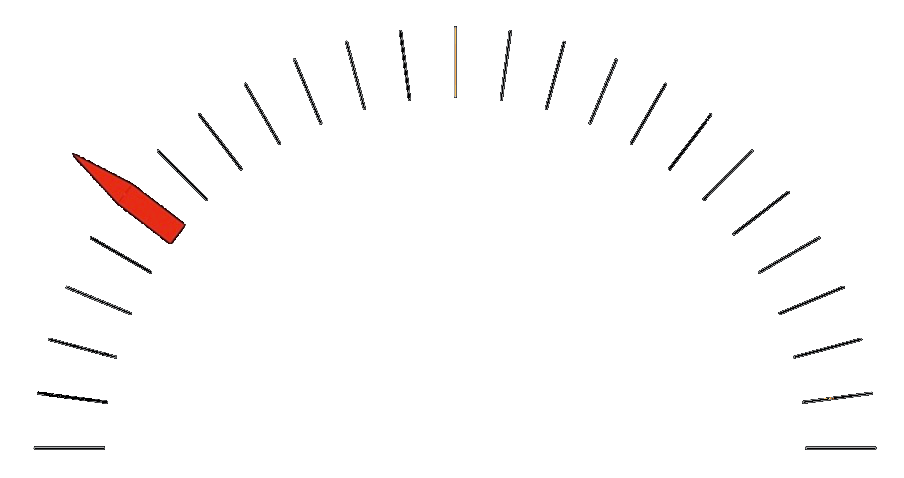

Benjamin Graham, widely regarded as the father of modern value investing, explains the dangers of liquidity and the concept of value versus price though the story of “Mr. Market,” a character in his classic book, The Intelligent Investor. Imagine that Mr. Market is your business partner, and each day he offers to sell you his share of the business, or buy your share of the business, at a different price. He tends to get over-emotional in reaction to the headlines of the day. And he’s constantly throwing numbers at you which represent his estimate of the value of the business you operate together.

Of course, you know the business well and have confidence in your opinion of what it’s worth. So on the days that Mr. Market is overly pessimistic, you should be buying his share of the business from him. On the days when he is extremely optimistic, you should be selling him your share. Graham presents Mr. Market as a character you can take advantage of to buy from when prices are attractive and sell to when they’re overly optimistic.

In Graham’s story, you are rational and levelheaded, while Mr. Market is wildly volatile and irrational… just like the actual market.

Now let’s flip the story around. The danger that most fail to realize is that Mr. Market just might be YOU! No matter how stoic you think you are, in reality your emotions are subject to change based on all sorts of factors out of your own control, and you are likely to make poor decisions as a consequence. And so having the ability to buy and sell at will, with negligible transaction costs, ultimately can harm your long-term investment returns. When you’re inundated with negative headlines and bad news, regardless of how rational you think you may be, you might just be tempted to sell your piece of a business for far less than the actual value.

Mirror, mirror, on the wall… who’s the most rational investor of them all?

We tend to operate in blissful ignorance of the value of our business, our home, or our real estate rental investments. You probably know a lot of people who have become wealthy by holding illiquid assets such as these over years and decades.

Imagine one bright, sunny day early in your business’s evolution, Mr. Market comes into work in a radiant mood and offers to buy your share for double what you think it’s worth. You just might accept that offer. But if the business grows over the coming years and decades, you would have been better off not selling to him at all. You might have gotten one over on him by selling him an asset worth $500k for $1M. But if the asset has grown over the years and is now worth $20M, who really won the trade? You may have won the battle on that particular day, but you lost the war.

And so even the parable of Mr. Market, revered by value investors for decades, leaves us susceptible to the temptations of liquidity and too focused on short-term price movements.

Let us not forget that in July 2006, a 22-year-old Mark Zuckerberg refused an offer to sell Facebook to Yahoo for $1 billion1. On that day, Mr. Market was wildly optimistic about the value of his business. But Zuckerberg knew that it had the potential to be worth far more.

Liquidity, by making it so easy to sell, can therefore cause us to make mistakes. Overtrading, or reacting to short-term market or economic news, is a surefire way of diminishing your total returns over time. Zuckerberg had temporary liquidity in his private company shares through the offer from Yahoo, and with his eyes firmly on the horizon, he refused to succumb to the billion dollar temptation. At its peak, his company was worth over a trillion dollars.

I’m not saying it’s always going to be the right decision to hold on, but if you have confidence in the long-term value of an asset, it’s probably best to take advantage of Mr. Market’s more pessimistic moods to buy more from him, but don’t be so quick to sell. And certainly don’t fall victim to his pessimism and believe him when he tells you the business is losing value when you know better!

Most of the value of a business comes not from near-term earnings, but rather from what will be earned well into the distant future (I walked through the math here). If you understand this, you come to realize that the vast majority of business and financial news is short-term noise, and doesn’t have any significant impact on the value of a company’s shares. It’s easy to think past the headlines when you’re making decisions about a business you control, or an apartment building you intend to hold through thick and thin, but much harder when you can liquidate an investment in minutes, without getting up off the couch.

This is why most investors are best served by thinking of their stock investments as illiquid. Just because you can buy and sell easily, doesn’t mean you should. This is a bit like sticking to your diet when you know there’s a box full of fresh pastries nearby. It’s actually easier if you’re working with a professional money manager, and I’d argue that’s a necessary element to investing wisely, especially if you are new to managing significant liquid wealth.

Whether your wealth is liquid or illiquid makes all the difference in the world. Remember the parable of Mr. Market. Don’t let liquidity force errors in judgment.