On investing versus speculation

In Security Analysis, the 1934 bible of modern value investing, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd made a clear distinction between investment and speculation.

An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.

Benjamin Graham & David Dodd, “Security Analysis”

Investing in common stocks now, perhaps more than ever before, necessarily involves an element of speculation. This is reflected in the historic swings we have seen in stock prices over the course of the past few years. A global pandemic, economic shutdowns, and unprecedented fiscal profligacy created an environment of tremendous uncertainty.

So how do we maintain a steady approach in the management of our portfolios – ensuring “safety of principal” and a “satisfactory return” as described by Graham and Dodd?

First and foremost is a requirement to focus on the long-term. As Graham himself said “in the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” It’s easy to get swayed by the talking heads obsessing over short-term inflation indicators, or the direction of interest rates. From month to month, the consensus on these matters changes with the economic winds. Thinking about what the world will look like 5-10 years from now can help filter out the short-term noise.

Next, we want to prioritize defensive investing to minimize the risk of speculating with investment capital. Here I’m not talking about minimizing stock price volatility (although “safer” stocks will naturally tend to be less volatile), but rather paying close attention to the relative stability of a business, the dependability of cash flows, and the strength of the balance sheet.

What Graham and Dodd tell us about investing vs. speculating

A strict interpretation of the Graham and Dodd quote which opened this essay can be interpreted to mean that a common stock purchase is always a gamble. This is, of course, true to a certain extent. In “Security Analysis” the authors lamented the lack of objective criteria to judge the investment quality of common stock purchases. They provided the following suggestion as to what “good” stocks might look like:

1 – Leading companies with satisfactory records, a combination relied on to produce favourable results in the future; or

2 – Any well-financed enterprise believed to have especially attractive prospects of increased future earnings.

After a few pages of trying to define exactly how the above criteria might be applied, the authors conclude that “our search for definite investment standards for the common stock buyer has been more productive of warnings than of concrete suggestions.”

Graham and Dodd go on to say that “An [investor] that can manage to get along on the low income provided by high-grade fixed-value issues should, in our opinion, confine its holdings to this field. We doubt if the better performance of common-stock indexes over past periods will, in itself, warrant the heavy responsibilities and the recurring uncertainties that are inseparable from a common-stock investment program.”

This is pretty amazing. Here they’re saying, essentially, if you can get by with bonds, just buy those and forget about stocks – they are too risky!

Their ultra-defensive stance is tempered somewhat, however, when discussing how an individual investor may want to protect himself against inflation: “there has been a strong common-sense argument for some common-stock holdings as a defensive measure.” [1]

As the above quotes demonstrate, there is no clear definition of what makes up an investment venture versus a speculation. Indeed, Graham and Dodd take an entire chapter to attempt to define a distinction.

First, they focus on the concept of safety. In order to qualify as an “investment,” there has to be some element of safety present. The next challenge is to attempt to define “safety” in an investment context.

The concept of safety can be really useful only if it based on something more tangible than the psychology of the purchaser. The safety must be assured, or at least strongly indicated, by the application of definite and well-established standards.

The safety sought in investment is not absolute or complete; the word means, rather, protection against loss under all normal or reasonably likely conditions or variations.

Understanding that common stock investing offers little scope for “safety” in the traditional sense, but unwilling to compromise on the concept of investment versus speculation, Graham and Dodd then make a distinction between intelligent and unintelligent speculation.

Intelligent speculation – the taking of risk that appears justified after careful weighing of the pros and cons.

Unintelligent speculation – risk taking without adequate study of the situation.

And as a final compromise, they admit that an intelligent equity investment may have elements of each of these.

At times it may be useful to view a purchase somewhat differently and divide the price paid into an investment and a speculative component.

It is important to recognize that “intrinsic value” is by no means limited to “value for investment” – i.e., to the investment component of total value – but may properly include a substantial component of speculative value, provided that such speculative value is intelligently arrived at.

The example given in the book is that a company’s excellent future prospects may support a value in excess of the intrinsic value. In today’s world, “intrinsic value” itself has become a more difficult concept to grapple with. The value of a company like Google or Facebook, for example, has nothing to do with factories or manufacturing equipment. For companies like this, intrinsic value is derived from intangible assets, which are much harder to value than a factory full of equipment.

So I would take Graham and Dodd’s approach and tweak it for the world we live in. An existing business which generates reliable cash flows could be valued as an investment, while an acquirer might also apply an additional speculative value to a new line of business, geographic expansion, or the application of a new technology.

What is important is that the investor understand what type of investment they are making, and apply an appropriate discount rate (and therefore, value) to each component of the business.

What does this mean? You might look at a company like Apple, with a very stable business selling computers, tablets, and phones on a regular upgrade cycle as a fairly reliable core business, and discount the cash flows from those businesses at a lower rate, representing its safety. You might then look at newer businesses like the Vision Pro headset as more speculative, and use a higher discount rate to value those. Then you can blue sky and think of the impact the company might have on markets like health monitoring or augmented reality, and apply an even higher discount rate to those enterprises.

In this way, a single investment can encompass both an investment and a speculative component. Of course, you are relying on intelligent capital allocation by management, so that the more speculative parts of the business don’t unduly drain the profits from the more reliable elements. This is where the subjective matter of management quality comes in.

The growth vs value fallacy

A value philosophy does not mean that you must eschew investments in companies that are young and growing; in fact, if you have special insight into an industry, or a high risk tolerance, or the position is an appropriately small portion of your portfolio, you may actually have a preference for this type of company. What it means, however, is that you are always conscious of the price you are paying, first and foremost. First be concerned with return of capital, and then worry about return on capital. Most importantly, a value investor must enter into every investment with a solid understanding of what can go wrong, and protect his or her interests in such a scenario. In my opinion, investing for growth and investing defensively are not mutually exclusive.

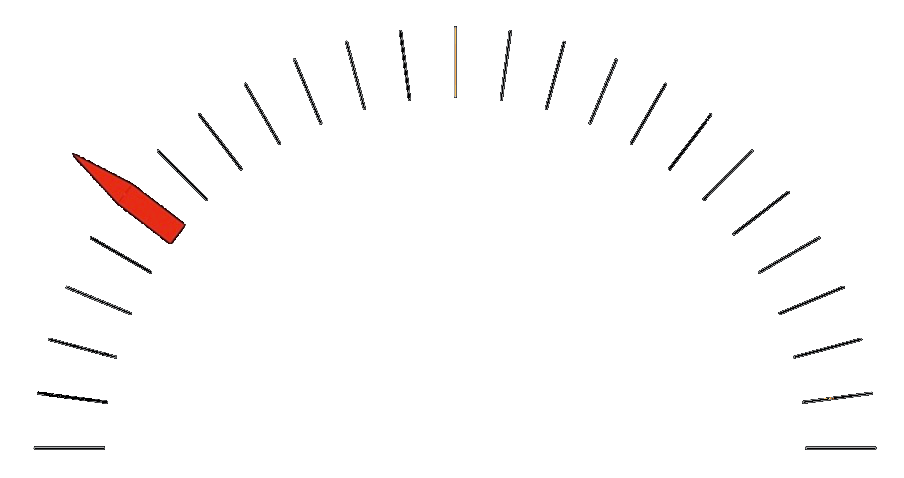

Investing defensively can cause you to miss out on things that are hot and get hotter, and it can leave you with your bat on your shoulder in trip after trip to the plate. You may hit fewer home runs than another investor… but you’re also likely to have fewer strikeouts and fewer inning-ending double plays.

Defensive investing sounds very erudite, but I can simplify it: Invest scared! Worry about the possibility of loss. Worry that there’s something you don’t know. Worry that you can make high-quality decisions but still be hit by bad luck or surprise events. Investing scared will prevent hubris; will keep your guard up and your mental adrenaline flowing; will make you insist on adequate margin of safety; and will increase the chances that your portfolio is prepared for things going wrong. And if nothing does go wrong, surely the winners will take care of themselves.

Howard Marks, “The Most Important Thing” Client Newsletter, July 2003

To most people, investing for growth might suggest a risky pool of assets, a good number of which could go to zero. On the contrary, every investment that goes to zero can erase the impact of a number of other successful investments. You do not have to be an early stage venture investor to create significant wealth; in fact, most angel investors are lucky to break even[2].

Balancing a defensive investment style with an entrepreneurial mindset

Entrepreneurs are optimists by nature. They see opportunity everywhere, and this is usually the key to their success. Value investors, on the other hand, are notorious curmudgeons. Their primary concern is what can go wrong. As Warren Buffett has famously said, “Rule Number One: Never lose money. Rule Number Two: Never forget Rule Number One[3].”

A 2012 issue of CFA Magazine has an interview with Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, where he discusses the risk of overconfidence and bias in making investment decisions. Here’s a perfect illustration of the dichotomy between the entrepreneur and investor mindset.

Optimism bias is not necessarily a bad thing. If a person is an optimist, it is certainly a good thing to know about that person. Optimists are happier than others and they may live longer. So, optimists are lucky to be optimists.

In addition, optimism helps people perform better. If a soccer team believes that it has a chance to win, even if they are the underdog, the team is likely to play better. On the other hand, and the example I always give, I have absolutely no interest in having an optimist as my financial advisor.

Seth Klarman expands on this by stressing the concern that value investors have with downside risk.

While most other investors are preoccupied with how much money they can make and not at all with how much they may lose, value investors focus on risk as well as return. To the extent that most investors think about risk at all, they seem confused about it. Some insist that risk and return are always positively correlated; the greater the risk, the greater the return. This is, in fact, a basic tenet of the capital-asset pricing model taught in nearly all business schools, yet it is not always true. Others mistakenly equate risk with volatility, emphasizing the “risk” of security price fluctuations, while ignoring the risk of making overpriced, ill-conceived, or poorly managed investments.

In point of fact, greater risk does not guarantee greater return. To the contrary, risk erodes return by causing losses… By itself risk does not create incremental return; only (buying at a low) price can accomplish that.

Seth Klarman, “Margin of Safety”

Having said all of this, there is certainly a place at the investment decision making table for a risk-taking, entrepreneurial vision. However, it must be tempered with a cautious outlook that is first and foremost concerned with protecting capital.

Investing as a business pursuit

There is no magic to this. Most entrepreneurs have experience in identifying undervalued assets and in creating value over and above the price paid for an asset. At its core, this is what value investing is all about.

It doesn’t have to be rock bottom to buy it. It has to be selling for less than you think the value of the business is, and it has to be run by honest and able people. But if you can buy into a business for less than it’s worth today, and you’re confident of the management, and you buy into a group of businesses like that, you’re going to make money.

Warren Buffett, from “Warren Buffett Speaks.”

Investing successfully does not have to be an esoteric exercise involving Greek letters and arcane formulas. At its core it is about allocating capital to the most attractive ventures, and this is an exercise in which most long-term business owners have a track record of success.

Investing is most intelligent when it is most businesslike. It is amazing to see how many capable businessmen try to operate in Wall Street with complete disregard of all the sound principles through which they have gained success in their own undertakings. Yet every corporate security may be viewed, in the first instance, as an ownership interest in, or claim against, a specific business enterprise. And, if a person sets out to make profits from security purchases and sales, he is embarking on a business venture of his own, which must be run in accordance with accepted business principles if it is to have a chance of success.

- Benjamin Graham, “The Intelligent Investor”

I am a better investor because I am a businessman, and a better businessman because I am an investor.

- Warren Buffett

[1] Reading this is somewhat surprising when contrasted with modern investment commentary, inspired by Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel’s famous book “Stocks for the Long Run,” which assures us that the risk borne by equity investors will be compensated over time with higher returns. There is, of course, no guarantee that stocks will outperform bonds over any investment horizon, no matter how long.

[2] Given the informal nature of the angel investment community, details are scarce (and unreliable), but a presentation directed at would-be angels at http://www.slideshare.net/venturehacks/how-to-be-an-angel includes quotes such as “Don’t do this to make money because you probably won’t,” “you’re a patron of innovation,” and “assume your investments are lost on the day you make them.” None of these quotes suggest that early stage investing is a cornerstone of a reliable wealth creation strategy.

[3] “The Forbes Four Hundred Billionaires,” October 27, 1986