Why investors underperform: the perils of chasing performance

Most fund managers will fail to outperform their benchmarks over time. But it’s even worse than that. Most investors will compound this failure by buying and selling at the wrong times, and by doing so, will further lag the underperforming funds they are invested in.

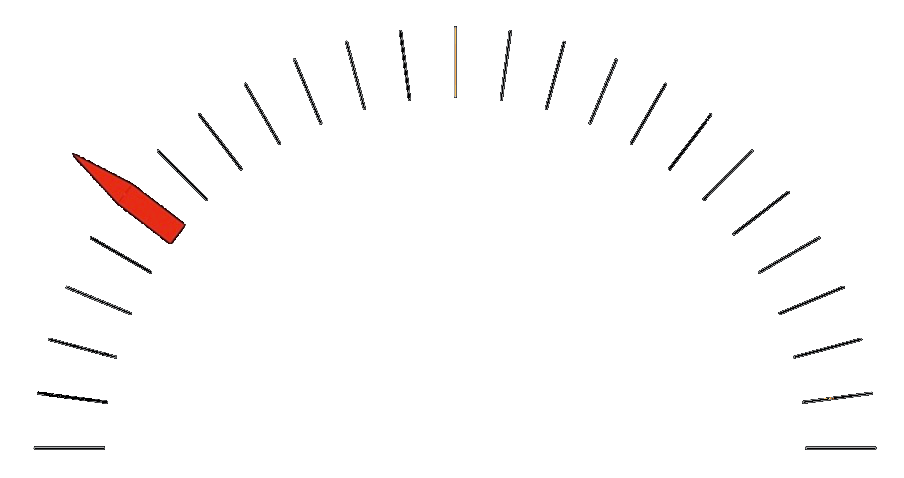

Carl Richards calls this the “Behavior Gap.”

This is another one of those timeless investment truths that we see play out time and time again. Chasing performance is a reliable path to investment failure.

This past week, the Wall Street Journal reported that Cathie Wood’s headline-grabbing ARK Innovation ETF had returned 11% annually since inception. I’m no fan of Ms. Wood’s, but this number is undoubtedly quite good (if you can ignore the gut-wrenching volatility experienced along the way).

But the real story was buried 18 paragraphs down the page. Despite the fund’s 11% annual gain, the average investor in this fund has lost 21% annualized on their investment.

“ARKK shareholders have not timed their purchases well. Many bought high and have yet to sell,” said Elisabeth Kashner, director of global funds research at FactSet.

Don’t cry for Cathie. She holds a majority stake in ARK Investment Management, which has earned $20 million in fees on the fund this year alone. It’s her investors who are left holding the bag.

I figured this was a good time to call up an excerpt from Low Risk Rules, where I discuss a similar hot fund from days past. The story is almost identical. Some things in this business never change.

The importance of conviction

Research firm Dalbar conducts a well-known survey that tracks the difference between market returns and those returns actually experienced by investors. The results are often striking. For example, in 2018 they noted that the average balanced fund portfolio returned 6.8% per year over the 20 year period from 1998 to 2017. During the same period, the average investor in those same funds experienced a return of 2.6%.[i]

How is that possible? Because investors buy when prices are high and the news is positive, and sell when prices are low and the news is negative. In doing so they ensure they will earn poor returns.

Many advisors use this data to prove to clients that they should stop trying to time the markets and stick to their investment plan. This is true.

But what if part of the problem causing this was a mismatch between the investor and their portfolio?

What if part of the reason they were selling is because they never really believed in their investment strategy to begin with?

A well known example is that of Ken Heebner’s CGM Focus Fund, the best-performing mutual fund of the first decade of the 2000s. The 10 year annualized return was an impressive 18.2%. In 2007 alone, the Fund was up 80%, attracting $2.6 billion of assets the following year.[ii]

And then… the housing crash. The mortgage and banking crisis. The Great Recession. Immediately following a huge inflow of investor dollars, the Fund declined 48%.

The money came in when the numbers were hot. But the investors didn’t truly believe in Heebner or his strategy. They were just chasing returns. And so despite the Fund having the best returns of any fund in the decade, investors performed horribly. According to Morningstar, the average investor in CGM Focus experienced a loss of 11% annually over the same time period that the manager made 18% per year.

There is no better illustration of why it’s important to avoid chasing returns. Know why you’re making an investment. Understand the strategy and have conviction in it. Because if you’re just chasing returns, you’re going to bail when things get rough.

Conviction is the key to investing successfully through downturns.

The long-term trend in the markets, as in the economy, is up. Believing this is a necessary prerequisite to investing in stocks. We all know what we need to do when the market corrects. When we’re facing a recession scenario, or a financial crisis. When everyone else is panicking and selling. We need to buy.

But human nature tells us that we’ll feel so much more comfortable running with the herd. And if the herd is selling, we also want to sell.

We will sell, even though we know it’s the wrong thing to do in the long run, because it will alleviate our pain in the short run.

So what do we need in order to prevent ourselves from selling at the bottom?

I’ll take it a step further—what do we need in order to buy more at the bottom?

The magic ingredient is conviction.

Conviction means that you have a firm belief in what you own, or in the strategy being implemented by your money manager.

It means that you won’t be tempted to sell when the market drops temporarily, no matter how violent the selloff.

In fact, it means that when that happens, you’ll actually be tempted to buy more.

I’m not talking about blind faith. I’m talking about having a solid understanding of what you own. Confidence backed by objective facts, not predictions of what other investors will do.

Conviction is the key.

[i] https://ca.rbcwealthmanagement.com/documents/48092/48112/influence-of-investor-behavior.pdf/00dadc04-e19b-407d-a32a-124edf1ad0f1

[ii] https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704876804574628561609012716